[Quoting Shakespeare] As flies to wanton boys, we are to the gods; they kill us for their sport. Soon the science will not only be able to slow down the aging of the cells. Soon the science will fix the cells to the state [‘return them to their original state’?] and so we become eternal. Only accidents, crimes, wars would still kill us. Eric Cantona, 29 August 2019, in a slightly off-beat speech, when asked what was going through his mind, on the occasion of him receiving the UEFA President’s Award 2019.

Theme of the month : Experimenting for longevity, right or duty?

Over the last few decades, societies have gradually developed a huge web of legislation to protect the health of people who undergo experiments; to a point that is no longer favourable either for medical progress or for people who wish to experiment for the common good.

Over the last few decades, societies have gradually developed a huge web of legislation to protect the health of people who undergo experiments; to a point that is no longer favourable either for medical progress or for people who wish to experiment for the common good.

Medical research in the past

For centuries, experiments involving humans were conducted with far less respect for the rights of the people undergoing the experiments than were accorded to other citizens.

The results of medical research starting from the Renaissance and especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries were extraordinary. But the lack of respect for the human rights of those undergoing experimentation was often also spectacular.

For a long time, very often, it was convicts who were ‘made use of’, cut up… At times when the death penalty was still common, this could be a way to escape the ultimate penalty. But this is all the more potentially unenviable especially since anesthesia had not yet been practiced.

In addition to those convicted by the courts, there were people with fewer rights, particularly from black Africa. For example, a doctor from the southern United States, James Marion Sims, James Marion Sims first experimented on black female slaves before operating on white women.

But when the subject of unethical medical experimentation is brought up, it is above all the atrocities committed during the Second World War, including those of the infamous Docteur Mengele, that we think of. He was responsible for dozens of deaths of women, children and adults. Those which were committed by doctors of the Japanese Imperial Army of Unit 731 are less well known. And yet the experiments were carried out under even more abominable conditions and caused thousands of deaths. What is more, most immorally, there were very few prosecutions after the war and no convictions of the main perpetrator Shiro Ishii.

It is these atrocities that were the trigger for strict legislation. But these developments were gradual. For example, until the 1970s the American authorities continued to experiment on African Americans.

The contemporary situation

Today, at least in the countries where the majority of medical experiments take place, legislation is very strict, mainly expressed in the Helsinki Declaration. By a kind of excessive pendulum swing, a person who is subject to clinical trials is better protected than an ordinary citizen. In order to carry out a trial, the organisation concerned must in particular be authorised to do so, the trial itself must have been accepted by an advisory body, and the “testers” must have given their « informed » consent, which means completing numerous and complex documents. It is also necessary, of course, that the health risk for these testers is not considered to be disproportionate.

Then the study itself consists of several phases. After establishing its probable safety, usually in animal trials, the same safety should be established in a group of people without testing efficacy (Phase I). Only then is the effectiveness of the treatment itself examined, first in a small group, then in a larger group, compared to another treatment or placebo (phases II and III).

The result of all this is that testing is extremely time-consuming and expensive. As very often trials are carried out by companies linked to the pharmaceutical world, investments are mainly made for patentable products and methods and with great difficulty for others. This explains, for example, why a longevity experiment on metformin took years to organize due to lack of resources.

However this slowness issue must be qualified. Accordingly, in the context of the Ebola epidemic some trials were carried out much more quickly. In the event, two aspects probably played a role:

- Fear of lethal consequences of the epidemic for the populations concerned and of the possible spread to other continents.

- And, in a much less ethically understandable way, a lesser concern for the rules of protection when the subjects of the trial are in Africa.

Areas for improvement: duty to share data and duty to experiment

At present, many people consider that medical data belongs to patients. Those responsible for carrying out the treatments could therefore not use them without consent. This is understandable when the data could be used « against patients », for example by an insurance company or an employer. But can the same be said for the results of medical research, which can be useful to everyone, starting with the weakest? Assuming that I possess a type of blood that is unique in the world because of its coagulating properties, would it be fair if I refused the use of this data, condemning people to death because they could not benefit from certain medical advances?

The answer should be obvious. Moreover, in practice, in the vast majority of cases, the formulas for consent to data sharing are bureaucratic red tape. It amuses lawyers above all, or more precisely, it provides them with a source of income without creating real consent, since almost everyone signs and almost no one reads it (and those that do read it will not make much sense of it).

In an ideal environment, the first question asked would be « How can we ensure that medical research allows a longer and healthier life for those who want it without harming those who provide the information?” All of us as patients would have a moral duty, even a legal obligation, to share our data. There would also be a strict obligation for organizations using the data to share results for scientific and therapeutic use and an equally strict prohibition on using the data for other purposes.

We would therefore all become testers without any additional effort, by pooling information on all aspects of the billions of medical procedures (surgery, drugs, tests, etc.) we undergo each year. This may seem worrying to some, but it can also be seen as reassuring because it allows more access to data and therefore more control. This sharing is already partially done in some countries, particularly in France. Indeed, much medical data is shared through, among other things, the National System of Health Data, but with an insufficient degree of accuracy.

It should be noted that this perception of the desired use of medical data is tending to spread quite rapidly, particularly in France. As medicine becomes more and more computerized, it depends more and more on accessible digital data. It is becoming increasingly clear that it would be immoral for a patient benefiting from the data of others to refuse to give theirs to others.

At the same time, however, medical trials will still be necessary.

A first means of acceleration could be self-experimentation. It has been quite frequent in the past and it still exists. For example, the controversial Liz Parrish as well as the renowned biogerontologist Greg Fahy have practised it.

But the main avenue is faster testing with more realistic rules on many aspects. It should be noted that speeding things up can be more of a guarantee of protection for those who will be the subjects of the tests. This is the case when information is shared more quickly, without being « blocked » because of rules on excessive appropriation of intellectual property rights or other reasons. What is needed, notably, is to have a more wide-ranging approach, ideally international, and to have a globalized ethical authorization procedure. Above all, what is needed is awareness of the urgency, once it is established that the probability of achieving the objective is no longer negligible.

Conclusion

Every day, 110,000 people die worldwide from age-related diseases. Effective testing must focus on the oldest (on young people, it would take years or even decades to see sufficiently convincing results). Elderly people should have the right to take part in experiments, and in better conditions. We may even consider that, for older women and men who are informed and who have the financial, social and psychological means to do so, it is an ethical duty; a duty of assistance of the same order as the duty we may feel to give our blood in the event of a disaster.

Good news of the month : Trials of metformin for longevity are about to begin. A trial with 5 « rejuvenating » products indicates a positive result.

The « TAME » project, that is to say a trial on positive effects of taking metformin by elderly people in good health is going to start in the United States. It is a piece of good news that must be tempered by the fact that this start has been awaited for two years now due to lack of funding.

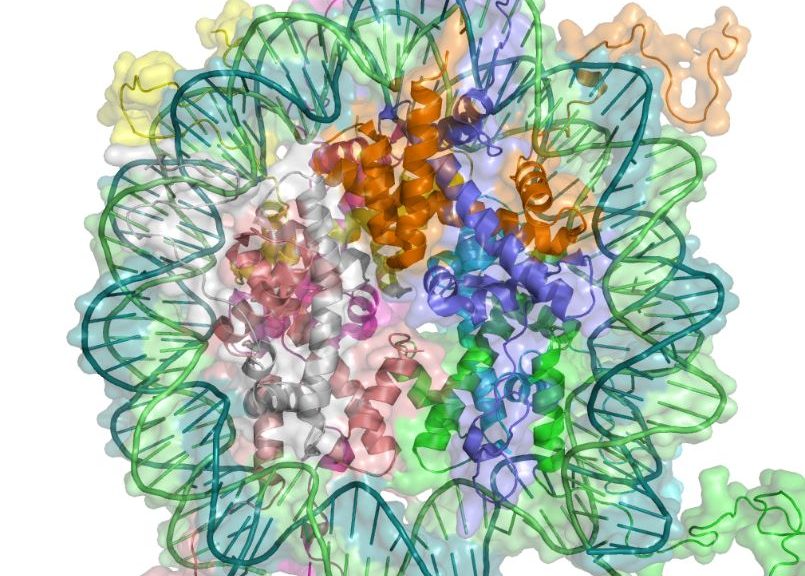

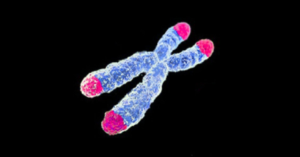

An extremely promising one-year trial of five products with a small group of men aged 51 to 65 has succeeded in establishing in this group a 2.5 year average increase in the age indicated by « epigenetic clocks ». In other words, it appears that rejuvenation is demonstrated over the two year period for people taking these products. This is extremely promising, but must be confirmed by larger-scale experiments.

To find out more :

- See : heales.org, sens.org, longevityalliance.org and longecity.org

Painting : La vaccine ou le préjugé vaincu, 1807 (vaccination, or prejudice vanquished).

Never ever, for the vast majority of humans and with regard to the vast majority of humans, will we wish another person dead.

Never ever, for the vast majority of humans and with regard to the vast majority of humans, will we wish another person dead.