There will come a time when our average life expectancy will reach 200 years. Masayoshi Son, head of the Japanese multinational conglomerate SoftBank.

Theme of the month: Living longer according to statistics

It was in London in 1854 in the Broad Street district. In the noxious  air of the metropolis, the inhabitants of the then miserable and overcrowded neighborhoods are dying in their hundreds from cholera. No one yet knows that it is a bacillus that is killing people, and among the most competent scientists many believe that it is the « pestilential » air (literally meaning « plague carrying ») that carries something that triggers the disease.

air of the metropolis, the inhabitants of the then miserable and overcrowded neighborhoods are dying in their hundreds from cholera. No one yet knows that it is a bacillus that is killing people, and among the most competent scientists many believe that it is the « pestilential » air (literally meaning « plague carrying ») that carries something that triggers the disease.

But a doctor, John Snow, asks to see the mortality statistics. He notes that deaths occur mostly in houses close to a certain well. He gets the well closed and mortality drops. It was perhaps the first time that statistics saved people, a century and a half before the reign of « big data ». And the statistics saved them despite a false belief. Indeed, Dr. Snow thought the water was poisoned. He did not know that cholera was a living organism (a bacillus). And so we see that, fortunately, it is not necessary to fully understand a public health problem in order to solve it.

Thirty years earlier, in 1825, a few miles from Broad Street, another British doctor had been the first to describe what is now known as the Gompertz Law. This is the exponential curve of death depending on age. In the 21st century, this exponential mortality curve has declined, but has by no means given way. In other words, today as in the past, mortality increases exponentially with age, but today the increase starts later.

The length of our lives is the result of countless events. When meeting people individually, the state of health seems to have no clear logic, from the century-old smoker to the muscular, diet-conscious sportsman who dies at age 50 from a ruptured aneurysm.

And yet millions of combined elements of our existence have a precise influence on average life expectancy. With regard to some of them, the reader of these lines has been a winner or loser since before he or she was born. For others, his or her choices will be decisive. However, our decisions are deeply influenced by our environment, whether social, economic, cultural, religious etc.

Hundreds of articles have been published on the consequences on longevity of certain products, social, cultural, economic and medical situations. A working file produced by the Heales association, entitled Longer life according to the statistics (and open to comments), provides a non-exhaustive, but already quite extensive list.

For decades, the observation of mortality statistics has led to improvements in health. It will most likely still allow for more. While it is almost certain that the detection of « good habits » and « good behaviors » will lead to only modest gains, the observations will most likely also open up avenues for further research.

However, great care must be taken in interpreting these observations, some of which contradict each other. Most studies are a posteriori behavioral studies. What appears to be favorable to longevity may in fact be due to other factors. For example, while it is generally uncontroversial that exercising is good for health, it is also uncontroversial that being in poor health makes exercise more difficult. As a humorist said: don’t sleep in your bed, statistically people die a lot there! To take another example, it appears that people who play golf and tennis live longer. Similarly, to give a more caricatural example, it is highly likely that people who regularly eat oysters and caviar and have a second home in Saint-Tropez or Monaco will also live longer. The causes of behavioral disparities are often primarily social.

Of course, scientists make efforts to « correct » the data by taking other factors into account before reporting the results. However:

- It is complex, particularly because the precise influence of other factors (social, biological, geographical etc.) is not known.

- It is tempting to settle for raw data (in the example cited, sellers of caviar and golf clubs will be tempted to settle for uncorrected data « demonstrating » longer life expectancy).

An ideal observation involves groups of people separated by drawing lots, each group should follow a different behavior (one group takes certain medicines, for example, and the other does not) and it should be carried out « double blind« .

Now here’s some interesting information about what has been found out. Some of the data will probably surprise you, but it should be interpreted with caution, as explained above.

Diet and other things taken in bodily

- Not being obese allows a gain of six to 10 years of life expectancy. Eating very little (caloric restriction) probably allows you to gain additional lifetime, but so few people manage to do so that statistics are lacking.

- At the same age, being vegetarian gives a probability of dying of 0.88 when we take the probability of a non-vegetarian dying as 1. The so-called Mediterranean diet seems to favor longevity, particularly olive oil, as well as chilis, green tea, coffee, chocolate and even a little alcohol (though this is controversial).

- As your grandmother may have told you: « Eat less, not too many French fries, a lot of fruit and vegetables, fish and little or no beef, not too much or too little carbs and all of that at regular times and not too late at night« .

- Being a non-smoker allows you to gain six to nine years of life expectancy. This is probably the least controversial precept for longevity. What is less well known is that tobacco kills more by cardiovascular disease than by cancers.

- If you can’t quit smoking but live in a place with little air pollution, you still gain almost three years of life.

- “Everything is a poison, (almost) nothing is a poison, it depends on the dose” (attributed to Paracelsus). Much of what is harmful in high doses is beneficial in small doses, this is the principle of hormesis. This could even be true for radiation.

Genetics

- All over the world, women live longer than men, in France, 5.9 years longer.

- « Choose your parents well ». Your longevity will be greater if your parents lived a long time.

- Have longer telomeres or otherwise the Serpine 1 genetic mutation.

- Be small (whereas, overall, the larger an animal species is, the longer it lives, within a species, small size is favorable).

Physical activities

- An hour of running may add seven hours of life.

- Playing tennis, squash or badminton is said to reduce mortality by 47 %. But if you reply : « poor people in bad health rarely play squash and badminton, my lord », you would be correct.

- Being an Olympic champion (or a chess champion) is said to allow a gain of more than seven years of life expectancy!

- Being nominated for an Oscar allows a gain of 3.5 years.

- Don’t sleep too little or too much, cycle, walk, run and do not stay sitting for too long. But do not break a limb during any of these exercises avoid too much sun, especially if you are Swedish ! Spend more time in the sauna instead.

Social, temporal and geographical

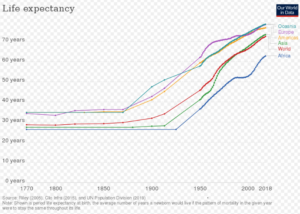

- It is better to live à Monaco or South Korea rather than Haiti or Nigeria. Life expectancy is growing faster in poor countries than in rich countries, but the difference between them is still considerable: up to 30 years.

- Live at high altitude, between 1,000 to 2,000 meters above sea level (two extra years) and near to green spaces (4 % less risk of dying).

- Not surprisingly: it is better to be rich than poor (up to 15 extra years in the most favorable cases). It is also better to be happy (20 extra months), smiley (7 extra years of life if you smile in photos!) optimistic (from 15 to 30 % chance of extra life) and to have a goal in life. And of course avoid being depressed (7 years less).

- It’s best to have a very conventional life : be married, study to an advanced level (3 extra years), go to church, have children (and having them after age 40, for a woman, adds 3.8 years of life !), with social and sexual relationships (50% reduction in mortality for British people aged 45-60), and you should also read books (23 months).

- But if you’re a man and all these beautiful images of traditional bourgeois bliss seem nauseating to you, you can try castration (7 to 11 more years). A little less drastic, using Facebook in California is said to decrease your mortality risk by 12%.

- And, of course, the more recently you’re born, the higher your chances of living a long life. Because you have had less time to grow older and also because life expectancy continues to increase in most countries of the world.

Drugs, healthcare and therapies

- There is no such thing as the longevity pill, but your doctor may advise you to take metformin, even if you are not diabetic, and advise you to take a low dose of aspirin.

- Do not change your doctor (20 % less mortality) but pick a woman rather than a man

But following the pro-longevity recipes won’t be enough for a much longer life.

Both in the field of therapies and drugs and in that of other various « methods » for longevity 1 + 1 does not make 2, but often hardly more than 1. And each « method » that is added probably leads to ever smaller gains. One example: getting more exercise, eating less and better and taking metformin should, if we add up the available statistical information, allow about ten more years of life.

It is probably much less, especially for people in countries with high life expectancy and who escape premature death. Indeed, unfortunately, when the age of 90 is passed (a little less for men, a little more for women), the « genetic lottery » is mostly the biggest factor. And even further, the maximum lifespan of 110 years remains an almost insurmountable limit, even for an individual who has followed a rigorous lifestyle all their life.

However, statistical information on longevity is giving us more and more clues as to what is useful, and the use of « big data » and artificial intelligence combined may facilitate medical research for longevity.

The good news of the month : More and more medical data available through research

It’s currently a major trend, and not just this month. Medical statistical data is increasingly available for health professions, citizens and scientists. The majority of managers and also of the public say they are in favor of data sharing for medical reasons (and not for commercial reasons) and this using high-performance IT resources. This is illustrated for example by the statement by French Health Minister Agnès Buzyn on 19 November 2019: « We must all work together to create the conditions conducive to the development of artificial intelligence in health. That’s why we wanted a health data platform. »

The official creation of the (French) Health Data Hub took place on 1 December, 2019. Certain changes in French bioethics laws that are underway also very probably herald easier and more effective research.

To find out more:

- See in particular : heales.org, sens.org, longevityalliance.org and longecity.org.

- Source of the image (Life expectancy by world region, from 1770 to 2018).